[Andy Miles] Hello, and welcome to “Resistance, Resilience and Hope: Holocaust Survivor Stories,” a podcast co-production of Illinois Holocaust Museum & Education Center and Studio C Chicago.

The mission of Illinois Holocaust Museum & Education Center is expressed in its founding principle: Remember the Past, Transform the Future. The Museum is dedicated to preserving the legacy of the Holocaust by honoring the memories of those who were lost and by teaching universal lessons that combat hatred, prejudice, and indifference. The Museum fulfills its mission through the exhibition, preservation, and interpretation of its collections and through education programs and initiatives, like this podcast, that foster the promotion of human rights and the elimination of genocide.

On this episode, we hear from Judy Kolb.

Judy’s maternal grandparents owned a fabric and dressmaking shop in Swinemünde, Germany, a fashionable spa town on the Baltic Sea. Their daughter, Carla, met a cantor named Leopold Fleischer in January 1937 when he moved to Swinemünde and rented a room in the same building. Carla and Leopold fell in love and married in the spring of 1939. By that time, the Nazis had begun encouraging Jews to emigrate from Germany, and when Judy’s grandfather, Julius, was arrested and imprisoned for six weeks in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp, his wife, Martha, insisted that the family leave Germany as soon as possible. She set her sights on Japanese-occupied Shanghai, an open port city which refugees did not need a visa to enter. To be able to afford passage there, Martha sold her house, clothing store, and some furnishings to a wealthy, non-Jewish neighbor. She bought tickets for the entire family on the German Lloyd Line. After obtaining exit papers to leave Germany, Martha presented the passenger tickets to the Gestapo at Sachsenhausen. Soon after, Julius was released from the camp.

In June of 1939, Julius, Martha, Leopold, Carla, and her brother Heinz embarked for Shanghai. The journey took four weeks.

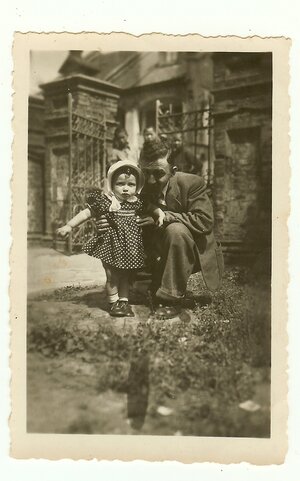

In Shanghai they were immediately taken to a Heime, German for “home.” Many Heimes were converted barracks crammed with narrow bunk beds, sleeping anywhere from six to 150 people a room. Soon, the whole family moved into an apartment in a small area called Hongkew. On March 6th, 1940, Carla gave birth to her daughter, Judith “Daisy” Fleischer.

Then, on December 7th, 1941, Pearl Harbor happened. The Japanese were at war with the United States and formed the Axis alliance with fascist Italy and Germany.

[Judy Kolb] So the following spring, in 1942, Colonel Meisinger came to Shanghai. He was called the Butcher of Warsaw. So he came to Shanghai and tried to convince the Japanese to somehow dispose of all the Jews living in Shanghai. Rumors were that they were going to put everybody on ships, send them out to sea without water, food, or whatever. There was even talk about crematorium being set up. Certainly they wanted to get rid of us. But what happened — the Japanese would not go along with the plan. So one of my saviors are really the Japanese.

[Andy Miles] Judy Kolb arrived in San Francisco in January 1948, nearly 8 years old. Soon after, her grandparents, parents, uncle, new aunt, and her aunt’s parents bought a home not far from the Golden Gate Bridge. In 1955, her father accepted a position in Chicago as cantor at a synagogue founded by German-Jewish immigrants who fled Nazi persecution. Upon graduating from Hyde Park High, Judy says she had “no inspiring ideas of what to do.” A friend was taking the entrance exam at South Chicago Community Hospital School of Nursing and suggested Judy come along. She did and ended up taking and passing the entrance exam herself, and entered the three-year R.N. program at the school. After graduating in 1961 and passing board exams, Judy started working in pediatrics at the University of Chicago hospital. Two years later, she married Louis Kolb, a resident in orthopedic surgery. Their first child, Jeffrey, was born in 1966. They had two more children and she remained home, doing volunteer in the schools and the community, later working in her husband’s office. In 2001, Louis died, and in 2003, Judy returned to working part time in a pediatric office, retiring in 2015. She started volunteering at the Illinois Holocaust Museum and Education Center when it opened in 2009.

Judy began our conversation talking about her parents. We spoke over Zoom.

JK: My father was a cantor. His life was his religion. He had so much faith, took great pride in being Jewish and leading that type of a life. And my — I always say my religion was listening to my father sing. That was my pride in going to temple was to listen to my father sing. So he was just totally committed to his faith, and family. Connection to family for him was very important and serving his congregation. So my father — just a kind, wonderful man. I adored my father.

My mother was only 18 when they got married; my father was 28.

My mother — her path in life was a little more difficult. She functioned wonderfully, but she had episodes of anxiety that got the best of her. But my father was just the most amazing husband. I had less patience for my mother. My father was incredible. They had a wonderful marriage, absolutely wonderful marriage. And he was the best thing that ever happened to her, is my — (laughs) — way of looking at it.

So life was going, not too much disturbance until 1938. So the thought of leaving — I don’t know. It may have happened, you know, little by little, but obviously, the Kristallnacht and all the horrors that went on then, they definitely knew that was the time to leave.

AM: And that’s when your grandmother sprung into action.

JK: Exactly. Immediately. Yeah. And in ’38, when she was doing all this, you could still get out of Germany, if you could find someplace to go. They were willing to have people leave to get rid of them.

AM: And the conundrum for so many is that there were so few places you could go —

JK: Exactly.

AM: — but it turned out the Shanghai was one of those places. But in order to go there, you really had to have the financial wherewithal in order to make that trip.

JK: You did. Exactly.

AM: So the city of Shanghai had unique circumstances that allowed this immigration. Can you talk about that?

JK: Well, it was an open port, which had been an open port early on since the Silk Road was established, and what I’ve read is nobody ever gave it a thought about closing. It never came up. So the port had always been open. May have been closed at some point, number of years, but it was still an open port. And that was the reason most people went there. They didn’t have to have documents.

But my grandmother did go to the local mayor’s office in Swinemünde and was able to get exit papers. So once she sold as much as she could, you couldn’t take any — funds were frozen. You couldn’t take any money out of the country, which they couldn’t use to spend on these tickets. So she had to come up with the money by selling everything. But anyway, she needed five tickets for my grandparents, my parents, and my uncle. And the liners, cruise liners, they were all cruise liners that were very expensive to go to that length. So they did get tickets on a German cruise line. So once she got all the paperwork together, she went to Gestapo headquarters. She showed them: “Here are our exit papers; here are the tickets. This proves we are leaving and you need to let my husband out of the camp.” And they did, because, I said, in those years, a lot of people, not enough, were able to get out of some of those situations, if they could prove that they were leaving Germany. So my parents were married at the end of May in 1939 and left a week or two later for Shanghai.

AM: So the Nazis, on the one hand, were allowing this departure, but, on the other hand, they weren’t making it easy —

JK: Oh, no.

AM: And they were going to deprive the family of any of its valuables and that sort of thing.

JK: Everything. Everything was inspected. And again, my uncle told me my grandmother hid some jewelry in one of the steamer trunks. So the Gestapo came to check everything. And he, being a young boy, was so nervous they were going to find it. I don’t know if it was that — they didn’t have many valuable jewelry to begin with, but it was something that you could probably bargain for when you got to Shanghai or needed some money. So that was not found.

So they were given — like you know, they were each allowed to take what was then $4, plus some clothing, furniture. I don’t know how they — if they took any furniture, but they could take a lot, but nothing of value.

My father was a little — story was a little more intense. When we were due to leave for Shanghai, my father tried to convince his parents to come along and she’d heard terrible things about Shanghai. She really didn’t want to go. I don’t know everything behind their thinking that they didn’t want to go to Shanghai. They wanted to go elsewhere. Wherever that was. Well, they never left. So they were sent to Auschwitz. And so was his sister. So because of that, I really never felt like I wanted to bring up the circumstances. And I just couldn’t talk to my dad about that. I knew, I’m sure, the anguish he felt because he tried to get his parents out when he was in Shanghai. And I didn’t feel it as a young child, obviously, but I just could not approach that subject.

AM: Is that something the family learned after the war?

JK: Exactly. There were loads of letters back and forth between my father and his mother.

AM: So when your family arrived in Shanghai, at that point, there was a process for taking in new arrivals, meaning that there was a — that they were taken to a Heime, and these were basically converted barracks crammed with narrow bunk beds.

JK: Exactly.

AM: But once they had been admitted and processed, it was a few years before a ghetto situation was imposed.

JK: Exactly.

AM: So your family was sort of taken in in these barracks.

JK: Yes. They — you’ll see pictures of trucks, open-back trucks, coming to the ports all the time to help the new arrivals, people who had already been living there. So when my family arrived, they went to the Hongkew area. They didn’t have funds. Some who came either had gotten funds sent from relatives in the States or elsewhere. So they actually could find apartments elsewhere, mostly in the international settlement. But then I arrived, nine months later; imagine that. Then they looked for other rooms. Then they moved to 83 Wayside Road, where they had one room that I slept in with my grandparents. And then there was a small kitchen, and a small bedroom where my parents slept. So most of the time there, we lived on Wayside Road.

AM: But you weren’t, at that point, crowded into a home with other —

JK: No. No. No.

AM: And so you were able to live a fairly normal life. Your family was —

JK: Well, I don’t think it was normal for them, although they got by; they did the best they could. It certainly was normal for me. (Laughs.)

AM: Because at that point, you knew nothing of normal.

JK: I knew nothing. I had my parents. I had my grandparents. I had my uncle. It was great. My uncle started a bakery. I could get bakery goods whenever I wanted. So it was all good.

AM: And your grandparents started a small transportation company, right?

JK: Yes. They initially met someone they knew from Potsdam who was doing that kind of work. So they joined him, and then I suppose he wanted to do something else. So he went and did whatever he did and they continued and called it Star Transportation.

AM: And what was that company involved doing primarily?

JK: As far as I know, everything was moved by carts. So they hired two or three coolies, getting the strongest Chinese men around, who were willing to work, who pulled the carts. So they would transport people, things — not people, things — especially like when they were transporting — I mentioned bags of rice and little smaller items. So it was mostly transporting items for whatever, in and out of the section for people who may need something transported when they were still working outside the area. So that was their business.

AM: When your family arrived, obviously they had sold off valuable things and then had been stripped of other valuables in the exit from Germany. But it wasn’t long, as you say, before your grandparents had a business and your uncle had a business. Was that facilitated at all through the community there?

JK: No, that was strictly their initiative. You know, again, my grandmother, everything was positive. We’re going to do this. Things were not expensive, obviously, in those days; whatever you bought in Shanghai was not expensive. So your living expenses, although they were dilapidated because that area of Hongkew was bombed out partly by the usual little war between the Japanese and Chinese, so that was certainly not a desirable place to live. And the Chinese, they were all poor, just getting by. So we were all kind of in the same boat. We were all doing what we can to get by, earn enough money to pay the rent, have food, and whatever else there was.

My uncle — my grandmother made it very clear to him that he was going to have to earn a living. (Laughs.) She wasn’t going to be supporting him. So he found a gentleman that was willing to pay the rent at a location and probably buy some of the equipment that was needed. And he was going to do the baking. And after — I think after — he called the original little place that he had the Daisy Café, and that was what they called me, for whatever reason; that’s my middle name, but I was known as Daisy. So this was the Daisy Café, but then he went on to open a bigger location.

All kinds of businesses were set up — restaurants, bakeries. So people, you know, did what they needed to do. And it also, obviously, helped all the residents. You could get kosher meats. I never ate in a restaurant and had Chinese food the whole time that I’m in Shanghai because it wasn’t kosher. (Laughs.) But you got what you need. You had to be very, very careful about what you ate. Water always had to be boiled. Everything — fruits, vegetables — everything got soaked in boiling water before you could eat it. So you had to be careful, but there was enough to eat.

AM: And during these early years of your time in Shanghai and the very early part of your life, World War II was, at that point, a European war, not expanding to the Pacific until late ’41.

JK: Right. As we all know, December 7th, ’41, Pearl Harbor happened. So the following spring, in 1942, Colonel Meisinger came to Shanghai, which we didn’t know anything about this. He was called the Butcher of Warsaw. So he came to Shanghai — first went to Japan, then to Shanghai, trying to convince the Japanese, who were the occupying — they occupied Shanghai, so we were under Japanese occupation the whole time we lived there — not the whole time; they obviously surrendered somewhere along the way. But at that point, they came — he came over and tried to convince the Japanese to somehow dispose of all the Jews living in Shanghai. Rumors were that they were going to put everybody on ships, send them out to sea without water, food, or whatever. There was even talk about crematorium being set up. Certainly they wanted to get rid of us. What the plan was, how to do it, I can’t vouch for. But what happened — the Japanese would not go along with the plan. So one of my saviors are really the Japanese, because if they had gone along with the plan, my family and I would not be here. So they did not go along with the plan.

AM: And why?

JK: I think the plan was over the top. It’s something the Japanese didn’t even want to do. They also wanted to keep somewhat diplomatic relationships with the Russians, so they didn’t want to get into that area to do those kind of horrible things. And there were a lot of Russian Jews living in Shanghai also.

There was never antisemitism. The Asians, the Chinese, the Japanese were not antisemitic. They kind of put them into being Europeans or whatever, and were always kind of impressed with what they have done over the many years. They certainly saw what the Sassoons and the Kadoories did; they brought a lot of money into Shanghai by setting up their hotels and businesses there. So they — I think they kind of respected the Jews that they knew.

So there was no animosity. So they really didn’t want to do that. You know, especially then in ’43, the ghetto was set up, which was kind of to appease the Germans — Japanese showing they’re doing something.

AM: So the request, so to speak, that was made to basically replicate the killing machine that was in place in Europe was rejected, but the Japanese did make the concession to the Germans to set up a ghetto —

JK: Exactly.

AM: — a designated area for stateless refugees, as it was called.

JK: Exactly. They called it stateless refugees arriving after 1937. Never mentioned Jews — “stateless refugees.”

The next — as you mentioned, the next problem was anyone living outside of that square mile, like at the international settlement or wherever they were living, had to move into that section. My family were already in Hongkew, so they didn’t have to move. So I myself didn’t feel like there was an influx of a lot of people, but I’m sure the adults felt that when everybody else had to move in. And the people that lived in the Heimes probably spent their whole time in Shanghai in the Heimes. But even though it was terribly overcrowded, there was always enough food. You know, the Jewish organizations in America and the Jews that came earlier to Shanghai that did so well all contributed to the food source for the people living in the Heimes.

AM: And one thing also in terms of this ghetto versus European ghettos: There was no barbed wire.

JK: No, there wasn’t. There were guards walking around.

AM: But there were hardships in the ghetto, obviously.

JK: Oh, definitely. Mostly it was — disease was very prevalent. My grandmother had dysentery and my uncle would go and try to find something to make her more comfortable. And the problem was there were doctors and I’m sure nurses, but there were not many medical supplies. That was the main issue. But obviously she got better. I had whooping cough, and I also had intestinal worms, which was very interesting. But again, you know, I got over. Nobody else in my family really got sick that I know of, except for the usual things. But the weather was terrible. It was humid, hot and humid in summer and, as I always say, hot — cold and humid in the winter. So lots of rain. So weather was a hindrance in things that you could do. Medical supplies were not prevalent. You had to be very careful, like I say, about what you ate so you didn’t get sick. But as far as anybody not having enough food, I never heard that anyone died of starvation. I mean, there certainly were deaths. People were older; people got sick and natural causes.

And of the guards — if you’ve read the books about Shanghai, there was one guard that everybody remembers named Goya. And he gave you your pass for the day. If you’re going out for the day, sometimes people had monthly passes. So when you approached Goya, he loved to put you through the ringer, you know, screaming or slapping you or whatever. And people would say that because he was short, he’d get on a table. So he called himself the King of the Jews and all that stuff. But everybody remembered Goya.

AM: Your grandfather was one of those people who had to leave the area for work. And you tell a story about a Japanese soldier who accused him of having improper documentation.

JK: Exactly, exactly. There was something that went wrong. The papers for a specific move was not filled out correctly or maybe not filled out at all. And there was — they realized what was happening. So they did put him in jail. I guess this was called bridge house. Everybody knew for some reason that it was a horrible place to be. I can’t imagine any jail would be a good place to be.

So again, my grandmother would send my uncle on his bicycle every day to bring him food and clean clothes. Luckily [he] was allowed to do that. So not sure the length of time that he was in bridge house, maybe three or four days. So the gentleman finally came forward to say that it was his fault. So they let my grandfather out of jail. And again, my grandfather did not say a thing about what it was like in there, and then I suppose nobody really wanted to ask. They didn’t want to bring up, you know, whatever was uncomfortable that he just went through. So he never spoke about that. He never spoke about the labor camp, but really was very content, you know, his whole life.

AM: So in addition to the sanitary conditions that you had to steel yourself against and try to stay healthy, there was another thing that you had to be fearful of as the war progressed and that was Allied bombings.

JK: Yes. And also, after the Japanese surrendered in August of 1945 — so, all of a sudden, they just disappeared from the ghetto. And, you know, nothing changed for people. They still weren’t going to go live anywhere else, but they disappeared. And then the other thing that happened: The American organizations that were sending food, they were no longer allowed to send things to a country, a section of the country that was being occupied by the Japanese. So there was a bit of a food shortage for a while.

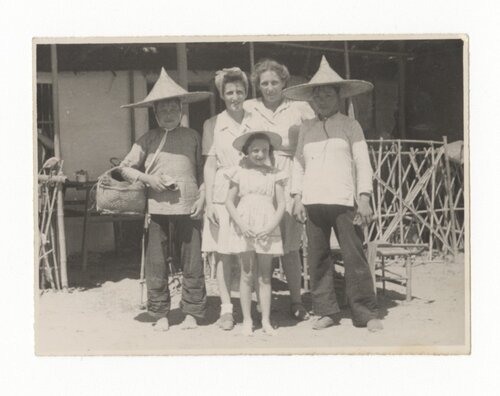

After the Americans became involved in 1945, yes, as you mentioned, as the planes flew over to bomb whatever they were bombing, one of them — one or two bombs did land in the Hongkew area. So there were 38 refugees killed and, like I mentioned, 4,000 — about 4,000 Chinese, some Japanese. So that obviously was very scary. It was not near where we were so nothing that I could see happened where we were, but there were — 38 of the refugees did lose their life at that point. But then there was more food being sent after that. So then, as the American soldiers were stationed in the area, there were more care packages being sent. So then things increased as far as food supply. And also a little bit of inflation started to happen. But it was more obvious to me — when the Americans arrived. I have a picture in a park that’s close by of a group of us little people with the American soldiers, which was something new for us. And I do remember the bubble gum, which came in a stick form — not in those really hard, round things you had to chew, but it was in stick form. And I do remember the taste of that bubble gum.

AM: And that actually gets us into something that we haven’t talked about too much, which is your own memories. And obviously, you were — the entire time during the war, you were less than five years old, or finally five years old in 1945.

JK: Right.

AM: Your memories, I’m guessing, are pretty few.

JK: Yes.

AM: But what sort of memories could you point to that could kind of give us a picture of your life in these years?

JK: Yeah. And I think we all have to think about what do we remember from the day we were born till you’re about seven years old. I mean, we all — it’s a little harder to remember way back then.

I do remember always being happy, obviously having my family around; that was wonderful. I did play with some Chinese little kids. There were vendors that would set up little stations right in the courtyard where we lived. So those people would always come by, set up their wares. They had little kids. So I remember running around with those little kids. You know, you didn’t have to know the same language when you run around and play with kids. I certainly have pictures of myself and Jewish friends.

When I started school and Horace Kadoorie set up a new building in the area or built something new in the Hongkew area, specifically for the schooling of the refugees that were there. So my father would walk me to school. I think I would — I started by myself and there were Chinese boys throwing rocks at me, what little Chinese boys will do. So from then on, my father would walk me to school every day. I don’t remember sitting in a classroom. I remember the playground because I fell off one day, landed on my nose. So obviously you remember pain. I remember the Hebrew lessons my dad gave me every evening. He was very strict. He had me in tears quite often. So I never learned to read German. German was my first language. The evenings were spent — instead of learning to read German, I was taught to read Hebrew. And once I started school, it was all in English.

So things, you know, were for me very happy. My aunt and uncle got married in 1946 in the temple, in the Hongkew area. That was exciting because I now had a new aunt, and her parents also lived in Shanghai. So they became part of the family. I did at one point — I must’ve been, I suppose, six years old. I was taking a bowl of soup off of a ledge that was too high and I actually burned my arm. So by the time they realized there was some damage there, they’re taking off — it was winter so they’re taking off a couple of jackets and all. So I do have a scar that I’ve had obviously my whole life. I do remember that was really painful. But what was interesting: Years later, I remember — they had called the doctor, obviously. They did whatever they need to do. So I had a white wrapping around my arm and remember years later, as a young adult, that I for some reason was proud that I had this wrap around my arm and I absolutely could not make sense of that. Obviously totally forgot about that over the years. Then when I started reading books about Shanghai, I saw a picture of Goya, the guard, and he had a white wrap around his arm to signify that he was a guard. He was obviously — those people were important that were walking around with those white bandages. So that’s why I was very proud when it got burned and I had a white bandage. So that connection as I got older was, you know, kind of amazing to me.

But I was a very happy child. I had no indication that my father was suffering about the state of affairs with his parents. That was never obvious to me. So it was a happy time.

AM: And as you said, your grandmother, who set the tone for the family, her tone was quite upbeat.

JK: Oh, absolutely. Absolutely. She was easy at making new friends. People came over; they had get-togethers. You know, always looking forward, never feeling that the world is against her, things are awful; always optimistic and cheerful and pushing people forward.

AM: You mentioned earlier that when the war ended, the Japanese disappeared.

JK: Yeah.

AM: But was there anything that could be called a liberation?

JK: Somebody didn’t come in and liberate us. What we knew and what — none of us, none of that group of people were going to be staying in Shanghai. They knew they were not going to spend their life in Shanghai. So as soon as they found out that they could possibly apply to get out of the country, they did. That group of refugees that came between ’39 and ’41, the Russians that came a little earlier than that — and the pogroms that went on in Russia — everybody that was Jewish and living around us would — did not — especially the European Jews were not going to be staying. That was just a flyover. They were not going to spend their life in Shanghai. So as soon as it became possible to apply to come to the United States, which is where my parents wanted to go — obviously, you know, people went elsewhere; they went to South America; they went to Australia; they went to Israel. So they started applying. So the Jewish distribution committee sent someone over to Shanghai to help with the paperwork. So besides the exit papers and the entrance papers, you also had to have a sponsor, which was either a Jewish organization or a relative in the United States, to make sure that someone would take care of you if you weren’t able to do so. So our sponsor was the Jewish distribution committee. But it took three more years after the war ended before we were able to leave.

AM: I know that you eventually did in 1948, January 8th of ’48, you were able to board the SS Marine Adder to San Francisco. What feelings did you have in leaving Shanghai, the only home you had known?

JK: Well, I think I certainly was apprehensive. The ship — don’t remember much except being terribly seasick for first couple of days, throwing up all over the place. Don’t remember much except for getting off in The Philippines and then in Hawaii and then finally supposedly looking for the Golden Gate Bridge, which you, of course, couldn’t see because it was foggy. So that was kind of a blur, except for those stops that we made. It wasn’t a comfortable ship to be on. It was a transport, so I’m sure accommodations weren’t very comfortable.

AM: And you were on it for four weeks.

JK: Yes. (Laughs.) Yes. You know, four weeks can pass quickly in a lifetime — (laughs) — so it’s four weeks.

Then my parents, my grandparents, my aunt and uncle and my aunt’s parents, the eight families, got together and we bought a house on 29th Avenue. So immediately, you know, there’s a bunch of kids on the street.

Then, at the age of 15, my father took a position in Chicago at a congregation in Hyde Park and we were moving, and I was devastated. I was angry. I was devastated. I didn’t talk to my father all summer, but later realized this was a perfect move for him. He taught in the school there. It was absolutely perfect.

AM: Judy, why do you tell your story?

JK: Well, like most people feel, it’s a story of the Jewish people being in great peril and the horrendous things that happened. And it needs to be retold. People forget very quickly. Needs to be retold and retold and retold. So many genocides since then. But the thought of 6 million — I have never been able to get my head around that number. How could someone, the beginnings of that horrible killing machine starting with one person, actually kill 6 million Jews and at least 5 million others? There’s never been something like the Holocaust, and people will forget over time. Flip the coin: Even one person that’s killed anywhere at any time is horrible, but 6 million just, I can’t comprehend that. So I feel it’s a story that needs to be told.

AM: Well, my last question is, what do you think the most important thing someone listening to this can take away from your story?

JK: You know, the one thing I will tell kids at the beginning is that I’m telling them my story, but absolutely everybody’s story is important. You don’t have to have a story like mine. To lead your life feeling that your life is important and hopefully you’ll do something that’s important, be kind to others, be good to your family. Like the museum says, if you see something wrong, be an upstander. Tell somebody if you can’t do something about it yourself. Just hopefully lead your life — I mean, when I’m thinking of going in the right direction, by being a kind person, doing the best you can. And the other thing I always mention to kids: I certainly tell them that my grandmother and my father were my heroes. So they need to pick their heroes carefully. It doesn’t have to be some superstar. It can be your mother, your father, your grandparent, an aunt, uncle, a teacher, whatever. There’s so many good people out there. Take the path of those people that have done well and have helped others.

I always — I told my friend the other day, my grandmother was my compass. What she did is something that I will never aspire to what she — aspire to what she — I’ll never accomplish what she accomplished and what she was able to do and keep the family together, keep everybody going. To me, she was amazing. And my father was just the kindest — even though he wanted a boy when I was born, I still turned out to be his favorite. So I absolutely adore my father. Always adored my father — again, the way he conducted his life. I wish people, everyone would follow those kind of lives of doing good for others, being kind to others, being kind to themselves, obviously also. So they, you know, they were my people in my life and they inspired me.

[Andy Miles] You’ve been listening to “Resistance, Resilience and Hope: Holocaust Survivor Stories,” a podcast co-production of Illinois Holocaust Museum and Chicago’s Studio C. If you’d like to learn more about this episode and the series in general, please visit studiocchicago.com/holocaust, or ilholocaustmuseum.org. And please share this podcast, rate it, and subscribe.

I’m Andy Miles and I’d like to thank executive producers Marcy Larson and Amanda Friedeman for their assistance and guidance in bringing this podcast to fruition, Judy Kolb for her time and candor, and I’d like to thank you for listening.

Photo credits: David Seide