Survivor Profiles: Walter Thalheimer

My purpose today is to plead with you not to repeat the mistakes of the past. If you see or hear of injustice of any kind, be it racial, ethnic, or religious, do not be quiet. Speak up; don’t stand aside and say, “it does not concern me.”

Walter Thalheimer

Walter Thalheimer was born in 1925 in Öhringenin, Germany. Walter had a happy childhood surrounded by family. His father and older uncle were both awarded the Iron Cross during their service to Germany during World War I, and the two of them owned a paint factory with Walter’s third uncle.

However, when Hitler rose to power in 1933, life quickly became untenable in Öhringen, a small town where Jews were easily identified. In April, Walter watched as all the men who were out in prayer clothes on Saturday were rounded up and arrested. His oldest uncle and father were soon released due to their service record, but they held his youngest uncle for three weeks and he was beaten and humiliated. Shortly after this, most of the town’s children joined the Hitler youth groups and began throwing stones at Jewish children in the street.

In 1936, the family moved to Stuttgart, a larger community that they hoped would shield them from what they had experienced in Öhringen. Life was good for a while, but before long, they began to see signs on parks and stores reading “No Jews and no dogs allowed.”

In October 1938, Walter was the last child to complete his Bar Mitzvah in the synagogue in Stuttgart. Weeks later, on “Kristallnacht,” the Night of Broken Glass, this synagogue was burnt down. Almost all Jewish men in the city were arrested and sent to concentration camps, but Walter’s father had a boyhood friend who had influence in the Nazi party, and he intentionally left Walter’s father off the arrest list. The American consulate even sent Jewish families seeking refuge on “Kristallnacht” to Walter’s family home to hide and keep safe.

After “Kristallnacht”, the school was closed due to intense damage, and Walter’s favorite teacher committed suicide. Walter’s family realized that they needed to leave. They found a few family members in the United States who were willing to help them secure their visas, and in April 1940, they began their journey to Rotterdam to board a ship bound for the U.S. Walter’s two uncles traveled separately, but both would escape and settle in Chicago.

Unfortunately, this was not the end of Walter’s family’s troubles: their ship was delayed in Rotterdam, and they were sent back to Germany. On May 9, they were finally able to cross into the Netherlands, but before they could leave, the Germans invaded. Walter was so traumatized from the bombing that he would jump every time someone moved a chair.

In September 1940, the family had to relocate to Maastricht. The Jewish Refugee Council there helped them avoid deportation and they stayed until 1942, hiding in underground tunnels from air raids almost every night.

In the summer, Jews were ordered to wear yellow stars on their outer clothing. Older Dutch people would give up their seats to people wearing the star on buses to show some solidarity, but the situation continued to deteriorate. In August, the remaining 500 Jews in Maastricht were deported to Westerbork transit camp.

Walter eventually found work as a page at Westerbork and used his position to defer his family and friends from deportation to Auschwitz. But in August 1943, Walter’s parents were sent to Theresienstadt as a “reward” for his father’s World War I service. In January 1944, Walter and his sister joined their parents at Theresienstadt, where Walter worked as a mechanic. Walter was shocked at how weak and sickly his parents looked when they were reunited. While they stayed in the camp, the Nazis made a propaganda film about Theresienstadt, and Walter had to pretend to drink coffee at a café they had built just for the film.

In October 1944, Walter and his father were loaded onto cattle cars and sent to Auschwitz. The conditions on the train car were unbelievably terrible. When they arrived in Auschwitz, Walter and his father were sent to different lines. A kapo told Walter that everyone in his father’s line would be gassed immediately, and that the terrible smell around them was coming from the crematoria.

Walter was forced to strip and had all his hair shaved off with a dull razor blade. He saw guards open people’s mouths looking for gold teeth. Every day, they had to go through “selection” and wait to see who would live and who would die. Walter watched people commit suicide by running into the electrified barbed wire at Auschwitz. The guards left their bodies there as a warning to the other prisoners.

Eventually, Walter was transferred to an ammunition camp near Leipzig to work as a craftsman. He saved a friend by pretending they were brothers. At this camp, Walter worked disarming unexploded bombs. Life was terrible in the camp, and the guards tortured them. Walter was only able to survive because another prisoner, an older German communist, shared his food and even gave Walter a new pair of shoes.

Walter soon needed those shoes. In early April 1945, he was again put on a cattle car train and traveled for five days with no food. Upon arrival in Czechoslovakia, American planes appeared and began shooting at German soldiers, so Walter and his friend were able to jump off the train and run until they escaped into the Ore Mountains.

They tried to hide in the forest, but they were recaptured and taken towards Carlsbad to be gassed. Walter and his friend waited for a moment when the guards were distracted, took their chance, and escaped back into the forest. There, they hid there for two weeks, living off grass and rotten potatoes. Finally, they came across two Czech women living in a farmhouse who fed them and pointed them to safety on the American side.

In early May, Walter returned to Maastricht and found that only five out of the 500 Jews deported had survived. One of the other survivors was his mother.

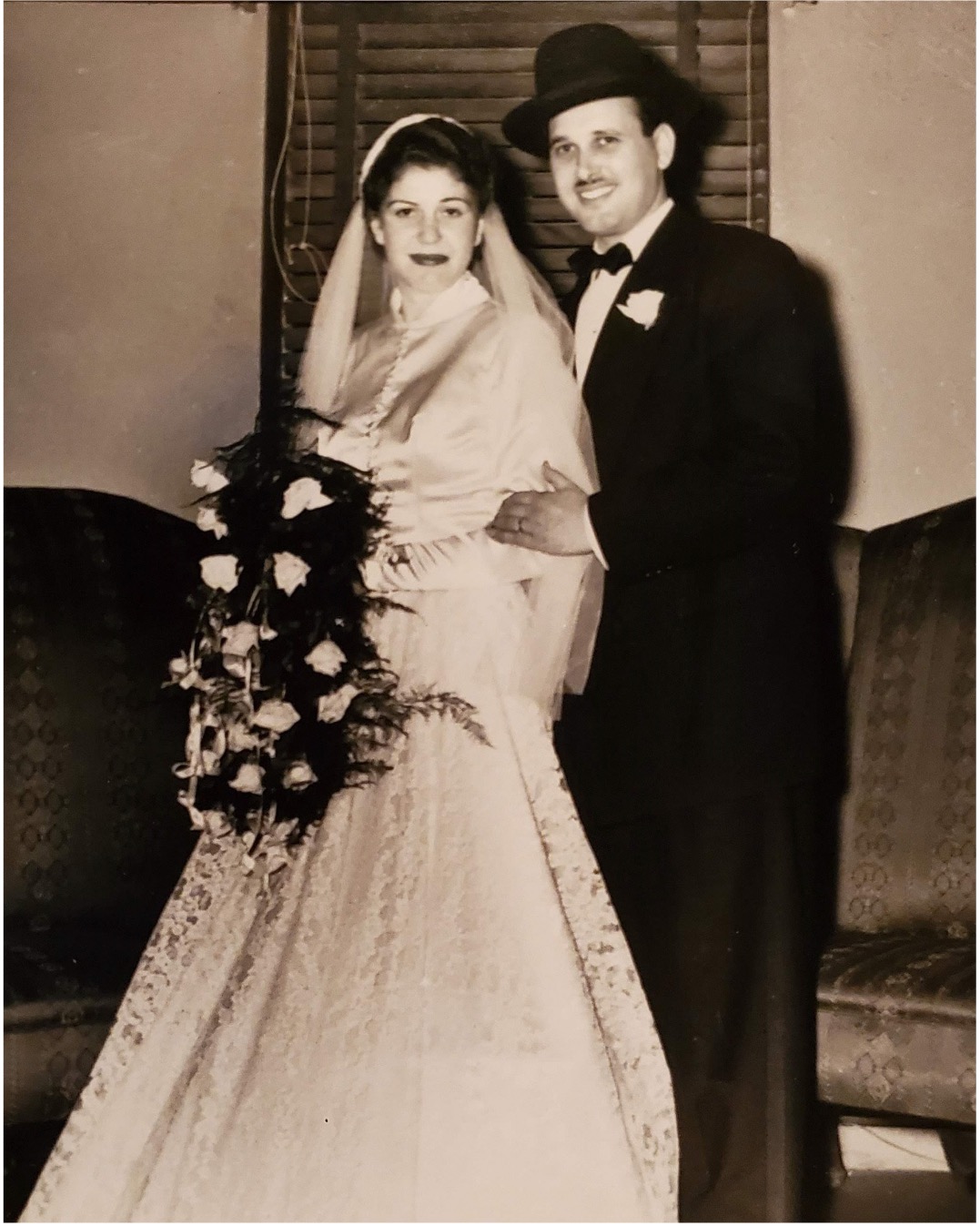

Walter and his mother immigrated to New York City in 1997. He met his wife, Eva, in 1950. They went out six nights in a row and Walter proposed on the seventh day. They married in September 1951, had two sons, and moved to Chicago to take over the industrial first aid supply business that his uncles had been operating. Walter’s mother passed away in 1986.

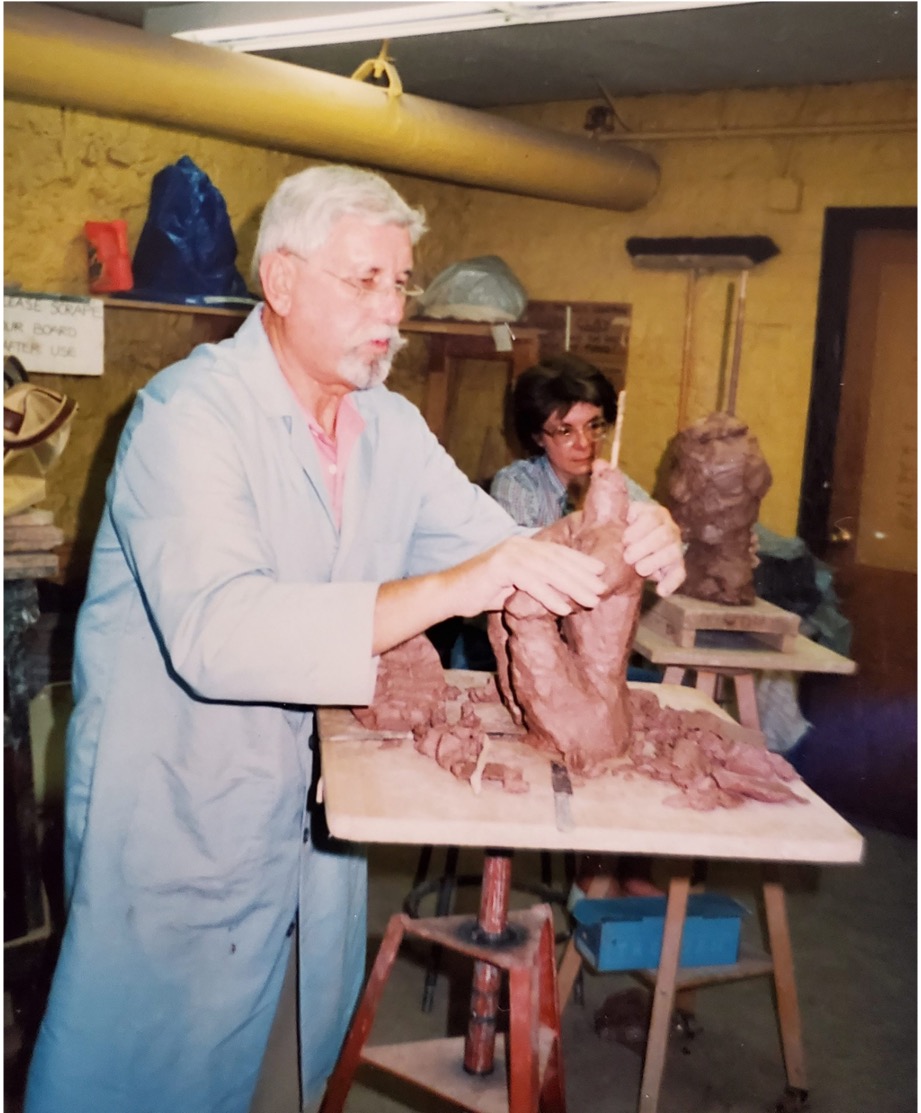

Walter never spoke about the Holocaust until deniers began coming forward. Walter knew he had to speak up and started sharing his story. He joined the Holocaust Memorial Foundation of Illinois Board (the Speakers Bureau) to share his experiences with students. Walter was also an artist and used his sculpture-work to express his memories. A clay menorah he created to represent the different phases of Jewish history is permanently on display the Museum’s library.

Before he passed away in 1997, Walter and Eva returned to Germany together. In the new synagogue in Stuttgart, Walter saw a piece of the old synagogue’s dome – the same dome he had made Bar Mitzvah under, preserved and built into the new wall. Seeing this small piece of his past that had survived the war alongside him, which he could now share with his wife and the renewed Jewish community in Stuttgart, moved Walter to tears.

Learn More:

Oral history interview with Walter Thalheimer Kristallnacht 83rd Anniversary Op-Ed from Walter’s grandson, Dan Thalheimer

Thalheimer family photo showing (left to right) Walter, his sister, his father, and his mother. Only Water and his mother survived their deportation and reunited in Maastricht, Netherlands. View this artifact >>

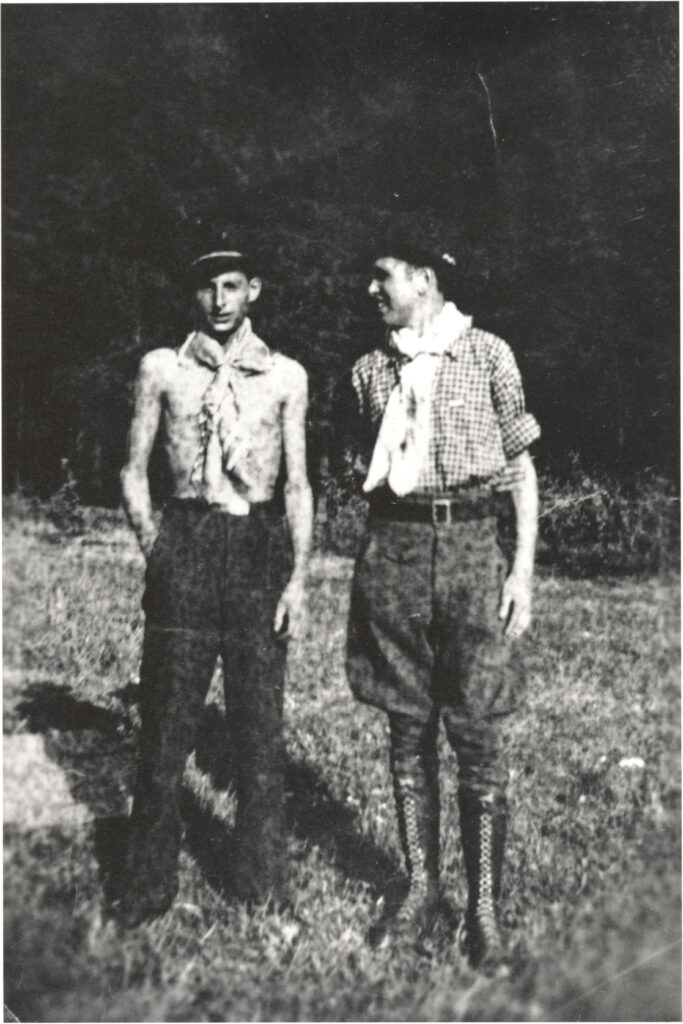

Frank Levita (left) and Walter Thalheimer (right) safe in Asch, Germany in 1945 after they spent two weeks hiding from Nazis in the woods. They each only weighed about 85 pounds by the time they reached the American side. Frank committed suicide several years after the war ended. View this artifact >>

Walter and Eva Thalheimer smiling on their wedding day in 1951. View this artifact >>

Walter smiles for a photograph with one of his many grandchildren on his shoulders.

Walter works in the ceramic studio. Ceramic artwork became an important part of Walter’s later life.

Walter created this ceramic menorah to show the different phases of history of the Jewish people. It is permanently on display in the IHMEC museum. View this artifact >>

Photo credits: Courtesy Dan Thalheimer