Survivor Profiles: Ernie Heimann

There is no denying what has happened. And we should learn from history and not repeat history. And because of that, if we learn from our history, we should make progress — maybe more slowly than is what would be desired, but we should make progress forwards, not to go backwards again.

Ernie Heimann

His Story:

Ernst “Ernie” Heimann was born on January 26, 1929, in Mainz, Germany. His father owned a tobacco wholesale outlet and a cigar factory, while his mother was a stay-at-home mother, and he had an older brother, Werner. Ernie’s early life was uneventful. He remembers wanting to be able to play with his brother and his brother’s friends. Everything changed when the Nazis came to power.

After taking control of the German government in 1933, the Nazis passed a series of laws restricting Jewish participation in civil society and public life. Ernie remembers not being able to go to the movie theater anymore, and the Nazis denying Jews education after the 8th grade in 1937. His brother, who was then in high school, had to drop out. A relative in Chicago suggested that Ernie’s parents send his brother to live in Chicago.

The night of November 9-10, 1938, a series of attacks on the Jewish community that would become known as Kristallnacht, or the Night of Broken Glass. Ernie’s synagogue and parochial school in Mainz were burned down. He saw the fire department standing outside of his school, watching it burn and not doing anything. They were there to ensure that the fire did not spread to “Aryan” businesses. His father did not return home that night. Some friends of his father’s told him it was not safe to go outside, so they had him stay inside. When his father got home the next day, he was shattered. He had believed that the Germans would never hurt him, because he served in WWI and had earned an Iron Cross, yet he saw other Jews who Germany rewarded for their service being beaten and forced to clean gutters. Ernie’s father realized that his family was no longer safe in Germany.

Ernie’s parents started to make arrangements for him to be part of a Kindertransport to the UK. On January 26, 1939, Ernie’s 10th birthday present was a notification that he was going to the UK on a Kindertransport. He wanted a bicycle, but he received a new chance at life instead. Soon after, Ernie’s parents bade him farewell at the Mainz train station. That was the last time Ernie would see his parents. When the train got to the border of the Netherlands, German police got on the train to see if they were approved to leave the country. When Ernie arrived, his aunt, Hede, met him and helped him get settled with the English family that would care for him. He learned to speak English quickly and resumed a relatively normal life. When children were evacuated from cities to the countryside, Ernie was sent to Northampton with 300 other children. He was made part of the Home Guard, the UK’s line of defense against the German invaders made up of WWI veterans and young boys. Ernie and the other boys carried messages between various locations of the Home Guard.

In 1943, Ernie received news he would go to the United States. He had an aunt there who was more than happy to take Ernie in. He set off for New York, the only child on a ship filled primarily with British sailors. The convoy of 300 ships was attacked by German U-boats in the North Atlantic; half the convoy sank, but Ernie’s ship was not hit. To avoid further attack, Ernie’s ship diverted to Halifax, Nova Scotia. He was placed on a train to Montreal, and eventually to New York, where his aunt met him at the station.

Ernie received a postcard that his mother had sent to a distant cousin living in neutral Portugal, which the German censors had allowed to go through. The card explained that the Germans had deported Ernie’s parents to the ghetto in Piaski, a town in occupied Poland near Lublin. Living conditions in the ghetto were terrible, and diseases like typhoid were spreading. That was the last anyone in Ernie’s extended family heard from his parents. Much later, during a trip to Germany, Ernie learned that all German records about his parents stopped at Piaski. They either died of disease in Piaski, or at one of the camps.

Shortly after his arrival in New York, Ernie’s aunt sent him to live with an uncle in Chicago, and he began his life in America. He graduated from Lane Tech High School and earned a college degree. In 1952, during the Korean War, the US Army drafted Ernie, and he served for two years. After his military service, Ernie got married and raised a family.

Ernie is an active member of the Speakers Bureau and continues to share his story with students visiting the Museum.

Learn More:

Survivor Speaker Session Coffee with a survivor facebook live session Podcast episode WBEZ interview

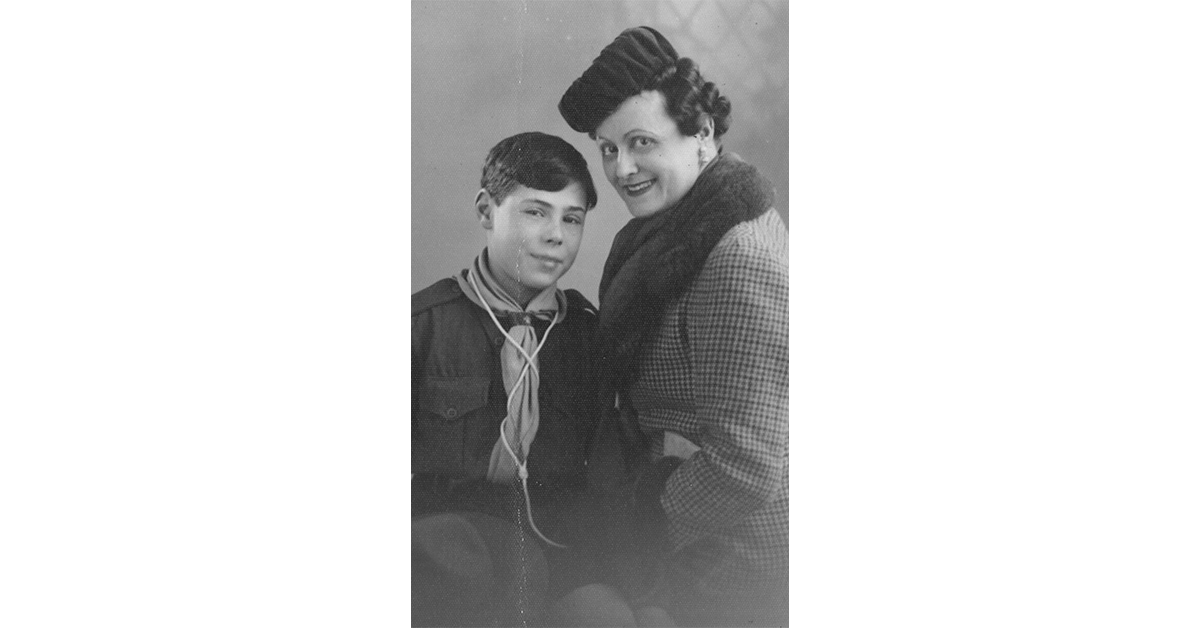

Ernst Klaus Heimann with his maiden aunt Hede, who sponsored him when he was brought to England on a Kindertransport in February 1939.

View this artifact >>

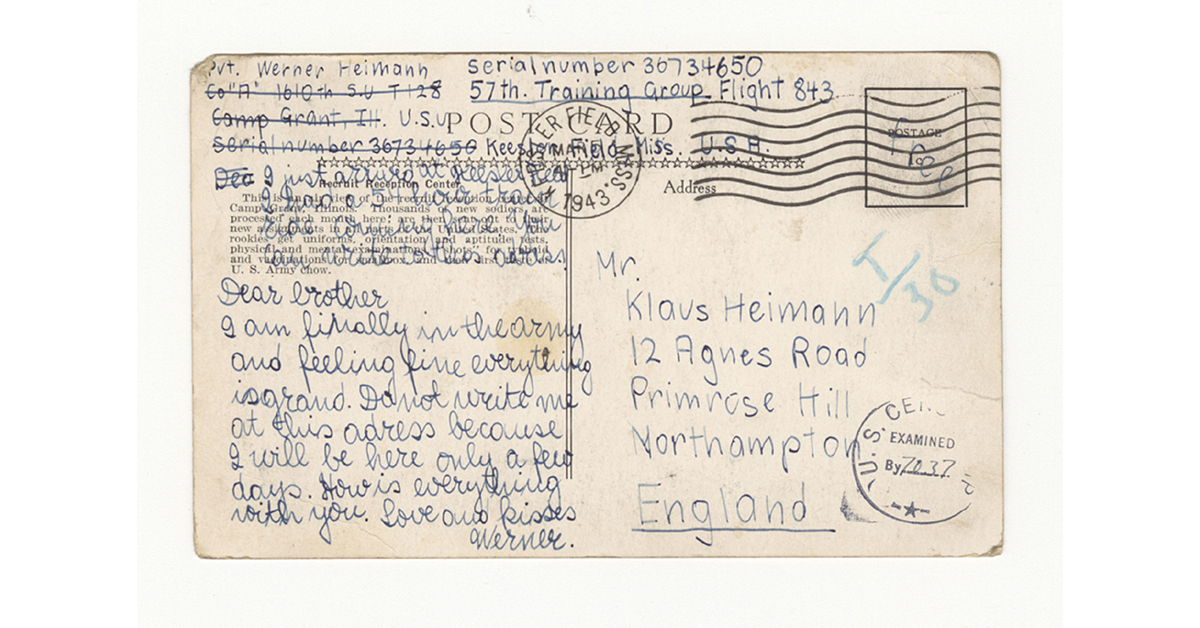

This postcard is from Ernie’s brother Werner who was in the US Army. Werner had immigrated to the US in 1937 to continue his education. He later volunteered for the Army Air Corps and because of that was given special dispensation to bring Ernie into the US, regardless of the quota.

View this artifact >>

Photograph taken in July 1939 when Ernst Klaus Heimann was living with the Silverman family outside London. The photograph shows (l to r) unidentified boy, unidentified woman, Renee Silverman, standing together outdoors. Inscribed at bottom: “Silverman / London, England July, 1939”.

View this artifact >>

Photo credits: John Pregulman