Survivor Profiles: Erna Gans

There are six million stories for the six million who were killed. There isn’t enough time in the history of the world to tell all those stories.

Erna Gans

Her Story:

Erna (nee Reicher) Gans was born in Bielsko, a town in western Poland adjacent to the German border, to a German speaking, Jewish assimilated family. When the war broke out in September 1939, Erna was in high school. Locals greeted the Germans with flowers. The family subsequently moved to Lvov, then on the Russian side of divided Poland. In June 1941, the Germans occupied Lvov. Erna used her knowledge of the German language to avoid deportation. She worked in cleaning homes that belonged to Germans, one of whom hid her, her brother, and her mother during one of the deportation actions. A few days later, another deportation took place, but this time the rescuer was out of town. Erna’s mother sent her daughter, who did not look Jewish, to roam the streets. When Erna returned, she saw her mother and brother on a lorry. They beckoned her to stay away. This was the last she ever saw of them. Soon after, Erna’s other brother was taken to the Janowska forced labor camp on the outskirts of Lvov, where he was shot. In November 1941, the Germans forced Erna and her father into the Lvov ghetto.

In winter 1942, Erna’s father paid a German to take her to Cracow and provide her with work and Aryan papers. She joined a group of Jews with fake papers who also worked for this man. Soon after, the group was denounced. By chance, Erna was not present when the Gestapo arrived. It was Christmas eve, and Erna was lost and alone. She decided to board a train to Zakopane, a Polish resort town in the Tatry mountains. On the train, she conversed with a Polish woman who offered her a room to stay. This woman later denounced her. In late 1943, Erna was arrested and sent to the Czestochowa labor camp, and from there to Plaszow. She was liberated by the Soviets in January 1945. Erna was the sole survivor of her family.

In 1946, she joined the Bricha organization, which organized illegal immigration to Palestine. However, her attempt to immigrate failed. She eventually arrived in Regensburg, where she met her future husband, Henry. They married in 1947 and moved to Chicago, where Henry had family. In Chicago, Erna earned an MA in psychology and taught at Loyola University. She had two children. In1978, she became the first woman seated as a delegate at the International B’nai Brith convention in New Orleans.

Following the attempted neo-Nazi march in Skokie, Erna became a founding member and the first president of the Holocaust Memorial Foundation of Illinois. She tirelessly advocated for Holocaust commemoration. Among her many achievements, she pioneered the first project of collecting and recording survivor testimonies from the many survivors who resided in the Chicago area. Erna was always committed to the cause of documenting the stories of survivors. Survivor Jerry Shane who immigrated to the United States with Erna on the Marine Tiger later recalled how she urged him to share his story with the other passengers.

Erna was instrumental for the founding of the first museum on Main Street. She was part of a group of founders who successfully advocated for the Illinois Mandate on Holocaust Education, the first of its kind in the nation, which passed in 1990.

Learn More:

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Testimony

Erna Gans (left) and her two brothers. Date Unknown.

View this artifact >>

Erna Gans and Skokie mayor Albert Smith. Third Annual Humanitarian Award Dinner. Rosemont, IL, 1988. Smith was crucial to survivors’ efforts to prevent the neo-Nazi march in Skokie.

View this artifact >>

Erna Gans and the founders of the Holocaust Memorial Foundation of Illinois, late 1970s. Top row, right to left: Erna Gans, Barbara Steiner, unknown, unknown, Mark Weinberg, Myrtle Figman, Al Lachman, Judy Lachman, unknown. Bottom row, right to left: Lisa Derman, unknown, Allen Zendel, unknown, David Figman, Aron Derman.

View this artifact >>

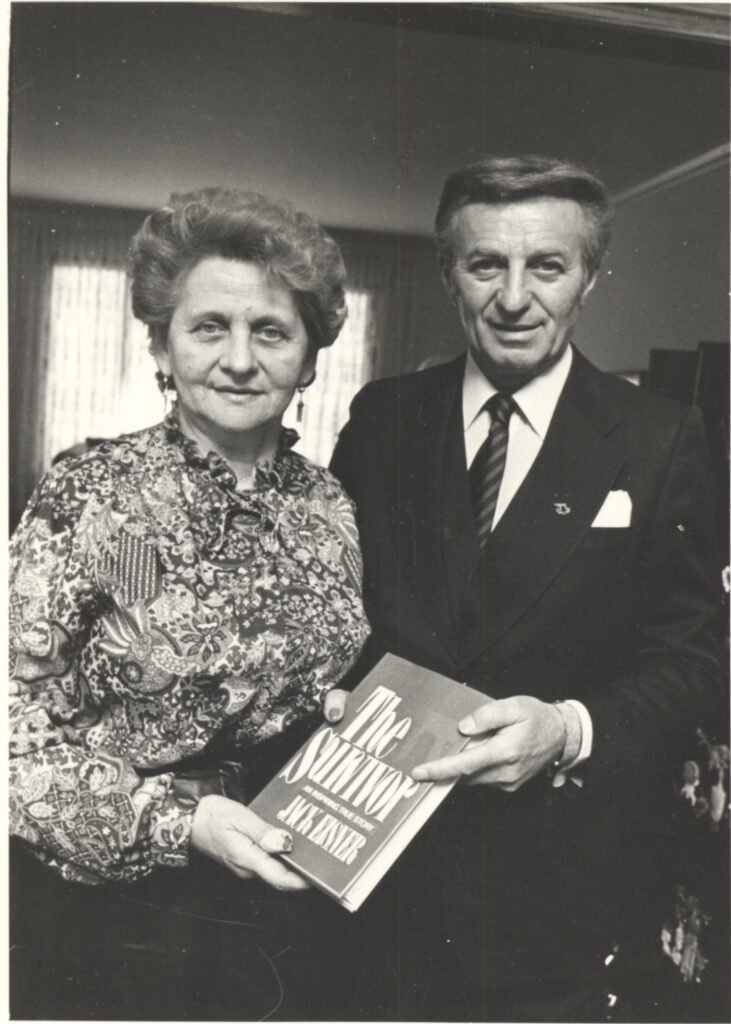

Erna Gans, founder and president of the Holocaust Memorial Foundation of Illinois (HMFI), together with Jack Eisner, president of the New York Holocaust Memorial Foundation. Late 1970s. Eisner supported IHMF in its early days.

View this artifact >>