Survivor Profiles: Barbara Steiner

We must make sure that our children, and our grandchildren, and the future generations will take the lessons from the Holocaust and realize that just with understanding, just with love and compassion, we can build a wonderful place.

Barbara Steiner

Barbara Steiner was born Bajla Zyskind in Warsaw, Poland in 1925. She lived with her parents and close by her two older brothers, her sister-in-law, and their baby, who was born in 1938. She had a large and vibrant extended family in Warsaw.

Barbara’s father had trained as a rabbi and dedicated his life to learning. He always encouraged his family to do the same, and took extra care of Barbara’s mother, who was frail from a childhood case of typhoid. Barbara adored her parents.

Life in Warsaw changed in 1939 when the Germans occupied Poland. Soon after, Barbara’s entire family was ordered to vacate their apartment with just a few hours’ notice. Food became scarce. Barbara’s oldest brother had to flee the city after someone denounced him to the Germans for trying to build a mill. She never saw him again. Barbara’s parents encouraged her other brother and his family to leave the city after the Germans beat him severely.

Jews in Warsaw were forced to give up their radios and telephones. They were banned from using public transportation and had to wear armbands with blue stars. In 1940, they were forced to build the wall around what would become the Warsaw Ghetto. The Jews were then forced into and unable to leave the ghetto.

Barbara fell sick in the ensuing typhoid epidemic. She prayed to God to live and finally recovered, but by that time, her father was also sick. Barbara tried to find a doctor, but the doctor told her there was no way to save her father. He held her in her arms one last time as he died. Two weeks later, Barbara’s mother also died. Barbara’s brother returned to Warsaw, but under the terrible conditions there, he soon starved. Barbara was then completely alone.

Barbara recalled that the most disturbing part of life in the ghetto was the way the conditions took people’s humanity away. Several times, she had to abandon others to save herself, including her mother and brother. These moments haunted her. But in other instances, Barbara was able to help young people hide with her or find work in the broom factory. She said she could hear her father’s voice urging her when to hide and when to run, and every time she listened to him, he kept her alive.

By 1942, most of the people remaining in the ghetto were in their teens and early 20s. They had learned from some of those who had escaped that Germans were killing people in camps. They began to organize, and Barbara joined Ha-Shomer ha-Tsa’air to help prepare for the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. She built bunkers, made Molotov cocktails, and trained as a medic.

On April 19, 1943, the Germans brought tanks to the broom factory, but the ghetto residents blew the first tank up and the Germans fled. When they came back, the Germans told them to surrender, but they continued to fight. They killed many German soldiers and hid in the bunkers, sharing food and tending to each other’s wounds, until the beginning of May. Eventually, the Germans began lighting buildings on fire, forcing everyone to flee the bunkers. Barbara was captured and put onto a cattle car. She said proudly of their resistance, “this little Warsaw Ghetto fought much longer than other countries in Europe.”

Without enough food, water, or air, half of the people on the cattle cars died before they reached their destination, Majdanek. When they arrived, the women were gathered in a huge hall and forced to undress. They were either sent to a shower or to the gas chamber. Somehow, Barbara survived, but she could smell the gas chambers and crematoria every single day in the camps. She described Majdanek as “a kind of hell” where they waited for their turn to die.

During the rest of 1943 and 1944, Barbara was moved to a series of work camps in Poland: first Skarzysko-Kamienna, and later, Czestochowa. When she and her friends were separated at Czestochowa, Barbara was so afraid that they would be killed that she started weeping. A young man came over and promised that he would help her survive. He helped her avoid work and brought food for Barbara and her friends every day. Later, when the man and his brother were scheduled for deportation, Barbara demanded her name be put on the list instead, and this action saved their lives. Days later, on January 16, 1945, the camp was liberated.

This man who had helped Barbara survive was Arnold Steiner. They walked out of the camps together with his brother, Joseph, and Arnold proposed to Barbara that very day. They married four days later.

Barbara and Arnold stayed in Czestochowa, where he was from, and re-learned how to be free together. In 1948 they had their son, Martin. Barbara named him after her father, Moshe, who had helped protect her so many times even after he died.

Barbara and Arnold soon decided that they had to leave Poland. In March 1950, they were given visas to move to Israel, but it was very hard for them to find work, and they often went hungry. So, in 1952, they immigrated to the United States and settled in Chicago. They worked several different factory jobs until Barbara was able to get an office job and earn her high school diploma. Though Barbara lost that job when her boss found out she was Jewish, she never stopped working for a better life. In 1962, Barbara and Arnold had their daughter, Muriel.

In 1972, Barbara flew to Germany to testify against several SS guard women who had tortured her in Majdanek Then, a few years later, when neo-Nazis tried to march in Skokie, Barbara gathered with fellow Survivors to discuss a plan to educate people about what happened in the Holocaust, so they could “counteract hatred with education and understanding.”

This group became the Holocaust Memorial Foundation of Illinois (HMFI), of which Barbara was a founding member and served on the Board of Directors. For many years, she was in charge of recruiting members, whose dues funded the entire organization. Her memories of life in Warsaw helped contribute to exhibitions about the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. She remained a fundamental part of HMFI and the Museum until she passed away in 2018.

Learn More:

Barbara Steiner Shoah Foundation Testimony Daddy Watched Over Me: Barbara Steiner’s Story of Struggle and Survival in Nazi Poland

Barbara Steiner and her husband, Arnold Steiner (Arie Szajnert) in Duszniki-Zrdpoi, Poland in 1947. The two met in a concentration camp in Czestochowa, Poland and helped protect each other from further deportation. Arnold asked Barabara to marry him the day they were liberated in January 1945.

View this artifact >>

Barbara Steiner in 1946/1947 in Czestochowa, Poland, where she stayed after Liberation. View this artifact >>

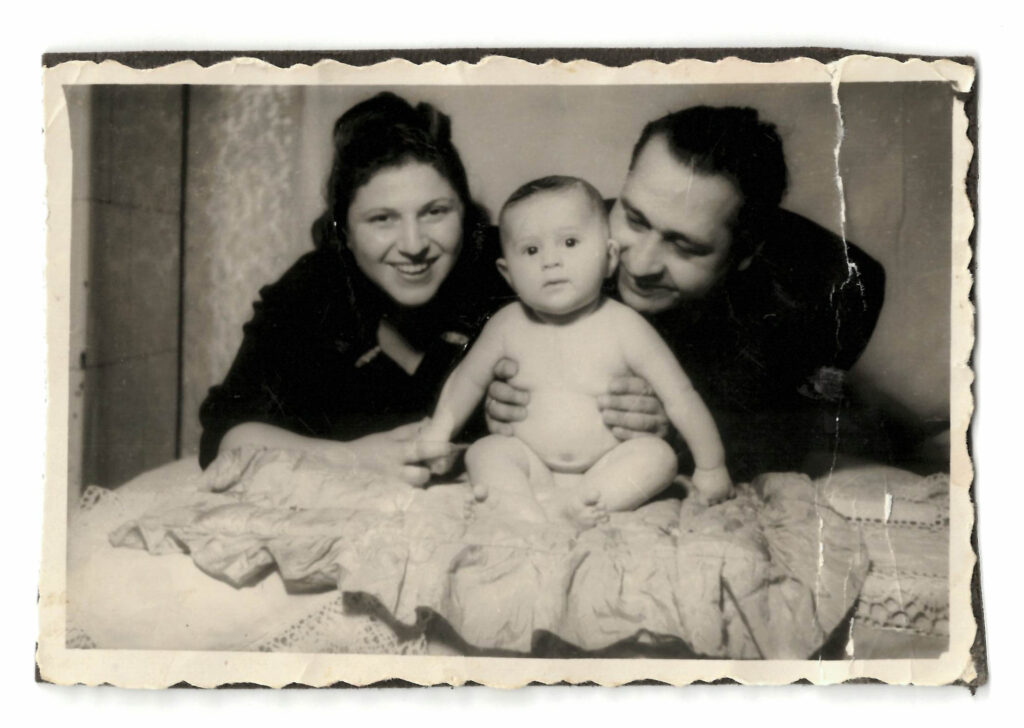

Barbara and Arnold Steiner smiling with their son, Martin Steiner, around 1948 in Reichenbach, Germany.

View this artifact >>

Barbara and Arnold Steiner with their daughter, Muriel Steiner Blumstein, in 1965.

View this artifact >>

Arnold and Barbara Steiner join the other founders in signing their names at the Holocaust Foundation of Illinois’ First Founders’ Meeting on June 29, 1983. View this artifact >>

Barbara Steiner and fellow survivor and founder Bela Korn pose together at the Holocaust Memorial Foundation of Illinois’ 2003 Board of Directors Meeting.

View this artifact >>